Free Education for All – The Ragged School Museum in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets opens its doors …

as published in ‘The Educator’ magazine

In June 2023, the Ragged School Museum opened its ancient doors on Copperfield Road, Mile End but its journey from being the largest Victorian ragged school in London which opened in 1877 has been a bumpy one.

Dr Barnardo took a 21-year lease on two canal warehouses on the Regent’s Canal in Copperfield Road for the purpose of opening the ragged school to two hundred destitute boys and girls and seventy infants. Its numbers would swell to thousands of children whose families could not afford the few pennies to pay for a Board School education. There were four paid teachers and six paid monitors. Each floor was made into a large classroom and the basements became covered playgrounds. It’s believed that the road in which it was situated was named after Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield as the writer was a close friend of Baroness Burdett-Coutts after whom the nearby Burdett Road was named.

In 1890 the London School Board abolished the Board School fee which signalled the end of ragged schools but the poorest children still flocked to the ragged school. Barnardo was known for helping the children find ‘a job for life’ on leaving the school as wood choppers and city messengers for the boys and work as housemaids for the girls.

The school, the largest of 148 ragged schools affiliated to Lord Shaftesbury’s Ragged School Union closed in 1908 when London County Council schools were able to meet the needs of the poorest children. The rag trade moved in until the 1980s. The warehouses were due for demolition in 1983 but local activists campaigned to save them and the Ragged School Museum Trust was set up. The site was then listed in 1985 as Grade 11 historic buildings when the Greater London Council Arts and Recreation Committee provided the funds to purchase the buildings and in 1988 work started on repair and refurbishment. In 1990, the site opened as a museum with exhibitions about the East End and the story of education and youth provision in London. Lady Wagner rang the old school bell which still, to this day, exists on the pediment and warehouse wall cranes.

Recently the museum has undergone much refurbishment with a 4.3 million grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund awarded just before the national lockdown. Meetings took place virtually and the museum has been open only for school groups but is now open to the general public. Victorian lessons for schools are recreated in one of the classrooms on the first floor and are led by an actor in Victorian costume: a way for children to discover how their great, great, great grandparents might have been educated through role-play, talks and hands-on exhibits such as slate boards and dunces’ hats. There is even a domestic kitchen as it would have been in 1900. The café in the basement, which once was the covered playground, has opened its doors for the first time to the canal towpath. The classroom is painted in the old ragged school colours: chocolate brown and primrose yellow.

The aims of the RSM are to save the building, to be open to the public which has wheelchair access and to exhibit and animate the world of Dickens and Doré through the stories of children who attended the school. The museum is keen to show how philanthropists, especially Doctor Barnardo and Lord Shaftesbury drove social change. The museum is a testament to that social change and shows the promise that the benefactors, teachers and children did two centuries ago.

There is an admission charge as the Museum has no core public funding.

The Director of the museum, Erica Davies says:

‘The Ragged School Museum is witness to the movement for universal free education, and a tribute to the men and women who struggled to achieve it. We urgently needed to repair and restore this important building and preserve the stories of the children that are part of its history and the community that surround it. It has been a huge challenge, particularly as we were hit with the first national lockdown, three days into the project in 2020. We’ve overcome challenges to expand under-developed areas, improved access and make it a desirable venue. With thanks to National Lottery players, we are delighted to be able to share the newly renovated buildings with everyone, we will be combining a strong education programme, with hireable-spaces and a new canal side café. We cannot wait for people to see inside in time for summer.’

www.raggedschoolmuseum.org.uk

Tel: 0208 980 6405

MUSEUM OPENING TIMES

Schools

For school bookings or for any enquiries regarding our Schools Programme, please email schools@raggedschoolmuseum.org.uk

Family/Holiday Programme (We won’t be doing this until next year)

For information regarding our Family Learning and Holiday Programmes, or our Sunday Open House, please email schools@raggedschoolmuseum.org.uk

Venue Hire

For any enquiries about venue hire, from photo and film shoots to paranormal investigations, please email erica@raggedschoolmuseum.org.uk

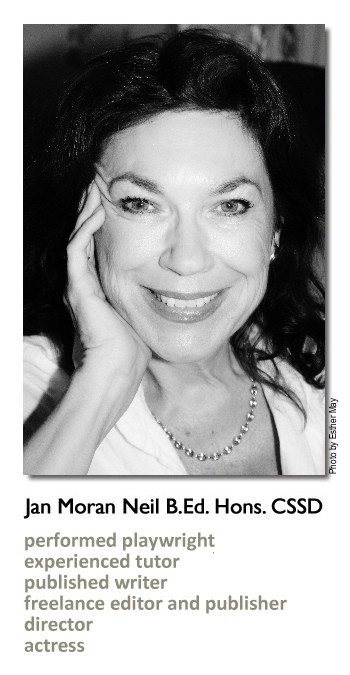

Jan Moran Neil

www.janmoranneil.co.uk

There are some great photos which I will be posting on Facebook and Instagram.